The Possible City:

Journey to Recover the Future

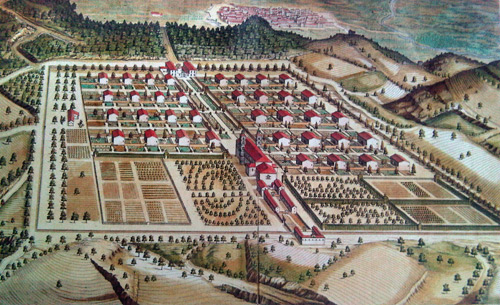

Author's note: The subject of this long piece is the interconnectedness of travel and imagining cities. One takes a journey; he also, at the same time, finds a new route home. I didn't know what was going on Out West when I wrote this, but it is not insignificant that it, too, is about expanding vision. Brad is wise to expand his as far he can, and likely someday it will to be to all of our benefit. For the time being, I present a different journey, one that, indeed, made me see with great clarity what lies right at our feet. Editor's note: It is indeed serendipitous that Popkin's epic essay is travel-oriented; it's also coincidental that he informed me of it before sending it to me -- but after I already knew my own travels had taken me in a different direction. That's life. On with Popkin and The Possible City . . . * * * by Nathaniel Popkin September 1, 2009 Part 1. Filadelfia [In Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, Marco Polo and Kublai Khan sit in the Emperor's garden. Polo recounts his journeys across Khan's empire.] Marco enters a city: he sees someone in a square living a life or an instant that could be his; he could now be in that man's place, if he had stopped in time, long ago; or if, long ago, at a crossroads, instead of taking one road he had taken the opposite one, and after long wandering he had come to be in the place of that man in the square. By now, from that real or hypothetical past of his, he is excluded; he cannot stop; he must go on to another city, where another of his pasts await him, or something perhaps that had been a possible future of his and is now someone else's present. Futures not achieved are only branches of the past: dead branches.When Calvino wrote Le città invisibili in 1972, cities everywhere were in decline. Venice, Polo's home and the book's foil, had long since devolved into a tourist icon, but the pace of change from perhaps the most brilliant expression of organic urban form to stilted commodity was accelerating. The city was also deeply decayed. Meanwhile, Calvino faced what seemed like a future world of endless megalopoli -- "a shapeless dust cloud," observes Marco Polo. "Traveling," says Polo to Kublai Khan, "you realize that differences are lost: each city takes to resembling all cities . . ." The only differences among them, he says, are the names on the map. The dual vision of decay and merciless expansion prompted Calvino's meditation. He no longer thought the city livable: so many "dead branches" (such evocative phrasing!), so many possible futures not achieved, opportunities squandered. Can a tree survive with so much dead weight? While listening to Polo, Kublai Khan begins to worry. To us, however, it sounds like a familiar question, one so often repeated. In the 1790s, when Philadelphia was the American capital, it was also the financial, intellectual, and culture center of the nation. Many Philadelphians, ignoring the political winds and the desires of the first President, wanted to keep it that way. They decided to build, at great public expense, a presidential mansion, at 9th & Market Streets. Surely, if we build it, they will stay. Both Washington and Adams refused to move in. The capital removed to Washington in 1800. Up to 1808, when the city's strong bid to regain the capital was narrowly lost, the empty mansion -- that early dead branch -- stood as cruel reminder. It's possible that futures not achieved are simply failures: a subway system invented but never built; a United Nation's headquarters thwarted; a Piccadilly Circus lost to a traffic circle; a Bicentennial planned and then abandoned; a shipbuilding deal arranged and then badly bungled. We might also see countless urban mistakes as lost opportunities. The state-sponsored monolith going up right now at Broad and Cherry (and without a green roof) is only one of many at present. But Calvino reminds us that all cities are inventions, reflections of desire, the product of choices. The city form, therefore, is not inevitable. Inside those choices, inside even forests of dead branches, there are possibilities. And so like Marco Polo, we take a journey. To relive the city's past? Perhaps. Like William Penn sometime in the 1660s, I come to Turin, in the Italian Piedmont. He saw a walled city of streets carefully laid out to intersect at right angles. During Penn's short stay there, Turin put a picture of urban order in his mind. For a future city planner, it was powerful antidote to chaotic London and Paris. When I explain this to the owner of Libreria Peyrot, an antique bookstore in Piazza Savoia, another customer interrupts, "Ah, yes, Turin engineering."  In the Alpine foothills nearby, Penn also likely saw the monastic community of L'Eremo dei Camaldolesi, three dozen detached houses and gardens situated on a generous grid and buttressed by square garden plots. If walled Turin is a model for Penn's plan for a "great city," then it's almost certain that Utopia-like L'Eremo is the origin of the Greene Country Towne. (These two things, so often conflated, are separate creations. The Greene Country Towne wasn't ever meant to be Philadelphia, but rather a template for farm towns related to both farm plantations and the city. The only one realized, apparently, is Newtown, in Bucks County.) Arriving in Turin, the original Italian capital, I see a gridded post-industrial city with a large, but walkable downtown. The streets are long and straight. Here, on humid July days, tall London Plane trees shed bark and the first brown, dry leaves. The summer light is bright and diffuse. Rowers grace an intimate river, the Po. The Piedmont itself, of gentle hills and vineyards, begins across the river. But for the slight glacial green, the Po is a Schuylkill doppelganger; the Piedmont, the fertile region that extends west across Pennsylvania, starts with the geological rise on the river's banks, in Powelton Village. (Penn was therefore justified in believing he could make wine in Philadelphia.) Bus shelter maps of Turin show the clearly highlighted rectangle of Center City, river to river, Vine to South Street. Wait, check again. Which city? "They are exactly the same," says writer and translator Cristina Vezzaro, from Turin, who stayed in my house while we stayed in hers. (You can find her blog entries on Philadelphia HERE.) Vezzaro refers to the scale of the two cities and the dimensions of the centers, and the quality of the space. I say intimate; she says cozy. The cities aren't, in fact, doubles; a more careful metaphor may be the relationship between father and son. In 1682, the sovereign masters of Turin published Theatrum Sabaudiae, a manifesto on the perfection of Turin engineering. Here, city planning, architecture, politics, and religion are combined in a "clear plan of communication," a grid of monumental buildings, arcades, and piazzas. The intent was to communicate power, wealth, and control. In 1682, that same year, Penn gave form to Philadelphia. It would have many of the same qualities as rational Turin, and also be a careful integration of city planning, architecture, politics, and religion. But sons often rebel against their fathers; they choose a different future. Philadelphia, then, would forcefully and consciously eschew monumentality in favor of republicanism, the power of the Court in favor of the rights of the individual.  The father-son relationship is complicated. The son finds himself unconsciously parroting the father. The father, now older, lives through the escapades of the son. Their

lives, anyway, mirror one another. And so it is with these two cities, emotionally intertwined, unnervingly akin. Both are historically the R&D labs of their nations, the

places where ideas emerge and things are invented. Often enough, the capital associated with those innovations leaves, and so both are second cities, and places of abandonment

and loss. They are conservative, backward-gazing, private places of restraint and aristocratic wealth and also, at times, the seats of jarring political upheaval. They have

been industrial and technological powerhouses, great magnets for immigrants. (The shared immigrant is a worker from Sicily, mistreated and abused no less in Turin in 1950 than

he was in Philadelphia fifty years before.) But these are mere generalizations.

The father-son relationship is complicated. The son finds himself unconsciously parroting the father. The father, now older, lives through the escapades of the son. Their

lives, anyway, mirror one another. And so it is with these two cities, emotionally intertwined, unnervingly akin. Both are historically the R&D labs of their nations, the

places where ideas emerge and things are invented. Often enough, the capital associated with those innovations leaves, and so both are second cities, and places of abandonment

and loss. They are conservative, backward-gazing, private places of restraint and aristocratic wealth and also, at times, the seats of jarring political upheaval. They have

been industrial and technological powerhouses, great magnets for immigrants. (The shared immigrant is a worker from Sicily, mistreated and abused no less in Turin in 1950 than

he was in Philadelphia fifty years before.) But these are mere generalizations.Early in the 1860s, with Turin as the new nation's capital and having enjoyed religious freedom since 1848, the city's Jewish community hired enigmatic architect Alessandro Antonelli to build a synagogue. Construction of a building to cost 280,000 lira began in 1863. Construction underway, Antonelli kept raising the height of the roof tower. By 1876, the unfinished synagogue, what Torinese scribe Giuseppe Culicchia calls Antonelli's "greatest folly," had cost the congregation 692,000 lira. It was already the tallest building in Turin. The congregation lost patience and the construction site sat idle. A deal was made to reconstitute the building as a monument to the first Italian unification king, Vittorio Emanuele II. Antonelli raised the roof again -- and again, and by the time it was finished in 1889, 26 years after construction began -- and after the architect had died -- the tower of the Mole Antonelliana reached 167 meters -- 548 feet -- the tallest masonry structure in the world. Ten years after construction of the synagogue began, architect John McArthur's plan for Philadelphia's City Hall -- what appeared to many a monument best fit for a king -- was approved. Still, the architect kept altering the design, particularly of the tower, and as each year passed the building became more expensive, a "marble folly," according to the Bulletin. McArthur died in 1890. Four years later, in 1894 -- some 23 years after construction had begun -- Alexander Calder's statue of William Penn was hoisted to the top, reaching 547 and 3/4 feet, not quite the tallest masonry structure in the world. "If on arriving at Trude," recounts Marco Polo to Kublai Khan about his experience in yet another city in the Tartar empire, "I had not read the city's name written in big letters, I would have thought I was landing at the same airport from which I had taken off . . . Following the same signs we swung around the same flower beds in the same squares . . ." To Calvino, the sensation is menacing. What if global capitalism erases all difference? He imagines a global dystopia. "You can resume your flight whenever you like," Polo is told, "but you will arrive at another Trude, absolutely the same, detail by detail." It may indeed be that global capital produces hierarchies of cities, that Turin and Philadelphia fulfill a certain, precise role in the production of wealth. But for the traveler far from his home city, the experience of encountering a parallel place is surprising, mesmerizing, alluring. The colors of Turin's flag? Azure and maize. It's the details that prickle. The cities expanded rapidly during the Industrial Revolution. From 1870 to 1930, Turin's population grew by 181 percent; Philadelphia's by 189 percent. At Midvale Steel, Frederick Winslow Taylor revolutionized the factory, "systematizing" the management of the shop floor; the year after Taylor died, in 1916, Giacomo Mattè Trucco installed the Philadelphian's ideas at Fiat's new Lingotto plant, the largest in the world. Industrial decline left both factories vacant and sent the cities spiraling. Turin's population fell 25.9 percent from 1970 to 2000, Philadelphia's by 22.1 percent during the same period. As loss and resilience frame the narratives of both cities, they don't account for everything. Turin is home to Juventus F.C., the New York Yankees of Italian soccer. Juventus is controlled by members of the Agnelli family, founders and longtime of owners of Fiat. The Agnellis are one of the wealthiest families in Europe. Like the Yankees, the Juventus fan base extends well beyond Turin. Unlike the Yankees, local support for the team is relatively small. Attendance is mediocre (this for the team that has won 40 Italian championships, more than any other). Emotional support rather goes to the city's other team, the second division Torino F.C. Why? They are upstarts whose string of championships in the 1940s helped to heal a place devastated by war. Critically, the championships were punctured by tragedy. In 1949, the team airplane crashed into the Superga, the cathedral that stands on a hilltop above the city. Nearly every player died. In 1976, amidst the unraveling of Fiat and the industrial landscape, amidst filthy streets and vacant factories and the scourge of heroine, glory came again. It was fleeting. They haven't been champions since.  To be a fan of Torino F.C. is to mythologize, to gaze backwards, to despair. The official team store is decorated with photos of the magic and tragic 1940s squad, and shelves filled with books on past glory. Fans gather at the team's elegiac field, long a ruins. It's called Stadio Filadelfia. (Stadio Filadelfia and indeed Stadio Olimpico, where Torino and Juventus play today, is on Via Filadelfia, named for Philadelphia.) If I stand in the center of that vacant lot, do I hear the grunts of Chuck Bednarik, imagine the grin of Bernie Parent, feel the whip of a Dr. J slam? Through the 1970s and 1980s, observers often noted Center City's empty nighttime streets. Stores closed early; there were famously few sidewalk tables. By the end of the 1980s, says Culicchia, author of Torino è casa mia, at night the streets of Turin's centro were mostly deserted. As Georges Perrier nonetheless saw Center City's potential (amidst what felt like an eerie urban desert) and opened the groundbreaking Le Bec Fin ("I changed everything," says Perrier), another immigrant French restauranteur, Rémi, transformed the Torinese night. "Rémi gets all the credit," writes Culicchia. In the late 1980s, he was the first to "intuitively realize the potential of a place like Turin." In mid-July, in Turin's lovely Piazza Carignano, where Italy's first king was born, a group installed an exhibit on contemporary architecture in Turin. I found the work on display weak, even boring. Very little felt groundbreaking, and this seemed to confirm what I had automatically assumed: like Philadelphia, Turin is strangled by the weight of a customary restraint and fear of bold ideas. This isn't uniformly the case, surely. In Turin, there are many exceptions, including parts of Renzo Piano's remake of the Fiat Lingotto complex and the contemporary Fiat factory, lauded for manufacturing innovation and design. But the Olympic architecture I saw is formulaic. (Stadio Olimpico, where Juventus and Torino F.C. play, notably opened the same year as Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron's groundbreaking soccer stadium in Munich.) Worse are the blocks of aggressively bland new apartment buildings replacing the ruined industrial landscape along the city's second river, the Dora. Torinese builders, too, make a habit of throwing up bricks. * * *  Part 2. Philadelphia "Sire, now I have told you about all the cities I know," says Marco Polo to the emperor Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities.Turin at heart is a cold, unforgiving, staid city. Many have used the same words to describe Philadelphia. But in Turin, quite unlike the comparatively garden and flower box crazy Philadelphia, there are tellingly few flowers planted in public squares or even on balconies, where pale green hanging sedum is preferred. This is in part why five hours east Venice startles. The Philadelphia that's missing from Turin is here in the intimate streetscape: seemingly endless vignettes of rowhouses and hidden gardens tumbling across the archipelago. "Do you see all those tiny houses in front of us?" asks Tiziano Scarpa, author of Venezia è un Pesce, "It's mad! All attached and yet each has its own little entrance! Now, as then, we live in this square observed by all, and at the same time each of those doors declares a desire for privacy."  Perhaps no one has made a more compelling observation of the emotional geography of rowhouse life. Sidewalk, stoop, doorway: each is a liminal stage between the purely public

and purely private realms. To live on a rowhouse street is to constantly navigate these borders. In the most emblematic example, where neighbors roam freely in and out of each

others' houses but are wary of strangers, the stoop boundaries are fluid and neighborhood borders carefully guarded. (Venice has always been governed in such a way.) One's

identity informs, and is reinforced by, the reputation and reality of the neighborhood. In Venice, says the late Philadelphia-bred New York Times architecture critic

Herbert Muschamp, "The result is a map where subjective perception and objective reality appear to merge."

Perhaps no one has made a more compelling observation of the emotional geography of rowhouse life. Sidewalk, stoop, doorway: each is a liminal stage between the purely public

and purely private realms. To live on a rowhouse street is to constantly navigate these borders. In the most emblematic example, where neighbors roam freely in and out of each

others' houses but are wary of strangers, the stoop boundaries are fluid and neighborhood borders carefully guarded. (Venice has always been governed in such a way.) One's

identity informs, and is reinforced by, the reputation and reality of the neighborhood. In Venice, says the late Philadelphia-bred New York Times architecture critic

Herbert Muschamp, "The result is a map where subjective perception and objective reality appear to merge." We all of us carry these maps, marked by personal experience and memory, by a sometimes conscious dialogue between our own private lives and the vast life -- past and present -- of the street. The city, in this way, becomes ours -- and we part of a landscape that accumulates time and people. Venice meanders through Scarpa, the author, just has he inhabits its streets. "I remember a game where we traced out a course with chalk in the lanes and campo and even into people's shops, and crawled along shooting corks ahead of us in a kind of race." Is it madness to stand in Campo San Sabastiano and see Fitzwater Street? Surely Kublai Khan wonders the same thing of Marco Polo. "The other ambassadors warn me of famines, extortions, conspiracies, or else they inform me of newly discovered turquoise mines . . . And you? . . . you return from lands equally distant and you can tell me only the thoughts that come to a man who sits on a doorstep at evening to enjoy the cool air. What is the use, then, of all your traveling?" Because rarely do the most piercing insights come from within. Clarity of thought and vision comes from broad perspective, from unexpected connections. Philadelphia -- what it is, what it might be -- reveals itself most forcefully from far away. With the Philadelphia Museum of Art in charge of the American Biennale exhibit this summer and fall, the connections are inscribed in the streets of the city. Only slightly lost inside the Giardini, Venice's lovely park, we came upon the American Biennale house from the rear, drawn into a little landscaped woods by the familiar neon of Bruce Nauman. "The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths," flashes the swirl-form sculpture, which in spirit might have been the work of Isaiah Zagar or the recently deceased Washington Square painter Tom Chimes. The artist, said Chimes, is meant to reveal "a truth and beauty beyond the realities of everyday life."  The Nauman exhibit, "Topological Gardens," is curated by Carlos Basualdo and Michael Taylor (who lovingly conceived and organized the 2007 Chimes retrospective), spreads from the United States Pavilion to two other locations in the city. In between is the thread of Venice itself, according to Basualdo, "as its systematic confusion between outside and inside, and private and public suitably interplays and dialogues with Nauman's works. It is there, in between works and buildings, where the viewer's imagination allows her to piece together her experiences, reinventing the work while traversing the city." She is, of course, step by step, also reinventing her city. It takes an intimate city, one accessible to the personal touch, accessible to time and memory, to bend in this way. Thus, even impermanent physical markings, like Scarpa's chalk cum memory, become indelible. Lasting ones, like Zagar's labyrinth of Bella Vista mosaics -- portraits and homages to people living and gone and assertions of poetic self-reference -- use and manipulate city space -- public and private, flat and topographical -- as a fluid medium. They are the product of an evolving dialectic between past and present, where loss and memory, as two forces aligned, are alive in the landscape. In Venice, two Philadelphia curators take this notion and turn it into international spectacle. Perhaps we don't need them. Late Friday afternoon on the island of Murano, a working class district centered on an eight-century-old glass-making industry, the sky is searing blue. Muscular former gondoliers and retired glass-makers take cover in a worn, wood-paneled bar. Fading twenty-year-old photos of the men climbing the Dolomites are tacked to the wall. Their wives in bright dresses chat dockside in what appears to be daily ritual. Rowhouses everywhere are shuttered and some are abandoned. Brown, desiccated flowers submit to the sun. Streets are aggressively, brutally quiet; glass stores -- with meager, dated displays that play on the Murano reputation and faded glory -- are empty. Clouds only amplify the sleepiness. Time endures this parochial hell, energy trapped in the listlessness. "Venice is not a sentimental place of honeymoon," says the Venetian Mayor, professor of philosophy Massimo Cacciari, in National Geographic. "It's a strong, contradictory, overpowering place. It is not a city for tourists. It cannot be reduced to a postcard." Near the Faro vaporreto stop, overweight teens plays sex-charged games with bottles of water. They dance their irreverence and uncertainty. Well before the coming inundation and hail, their cackling laughter is the only sound to fill the street. * * *  Part 3. New Philadelphia "In Maurilia," recounts Marco Polo, "the traveler is invited to visit the city, and, at the same time, to examine some old postcards that show it as it used to be: the same identical square with a hen in the place of the bus station, a bandstand in the place of the overpass, two young ladies with white parasols in the place of the munitions factory . . . ."Imagining the form of the future city, Calvino wonders how at present our desires account for the past. Do we believe a city is bound by its past glory -- or tragedy? That's the long-time fear in Venice, where the residential population continues an "inexorable" decline, to below 60,000. Annual tourists outnumber residents 350:1. Many see Venice therefore as a kind of urban museum -- depicted -- frozen -- not quite as it was but as an image of what contemporary tourists would like it to be. Those left, like the bored teens of Murano, inherit a place that has lost its threads to the future. Do cities, as products of desire, expire, as Maurilia, only to be replaced by each subsequent generation, one city after the next in endless, disconnected succession? In other words, can a city become something much different, perhaps even the opposite of what it was? The British writer Neal Ascherson says this is just what's happened to London. In 19th century London "nothing much ever changed . . . [A] deeply conservative, law-abiding society," it was "impervious" to even major economic upheaval. "Now," he writes, "everything is different. It's change, not permanence, that makes London famous . . . London has accelerated through ghetto multiculturalism to become one of the most adventurously hybrid cities on earth." But the past -- so alive in the cityscape, so present in our collective memory -- feels intractable in Philadelphia. It beguiles, and we can't quite let go. We push it away but can't resist. We egg it on, resurrect it, employ it willfully. In the popular marketplace -- among builders, tourism marketers, even municipal policy experts -- its the most valuable commodity we have. The rowhouse form, therefore, barely advances. Brick is an inane material in a hot, wealthy city in 2009. Yet it's become the visual symbol of revolutionary virtue. It is Philadelphia. So we paste it on as if to prove authenticity. If, as the Venetian Mayor Cacciari claims, the past isn't only commodified dead weight, but is rather something more powerful -- or powerfully contradictory -- can it be seized to define a future? How? No one in Venice, it seems, has figured that out. Calvino despairs. Amidst the haze of the infinite megalopolis, he sees also danger to humanity. Trude, Leonia, Procopia, Cecilia. These are some of his "continuous cities." Cecilia, for one, "is everywhere," an endless concrete jungle, ugly and inhumane, indeterminable from the next city. This, he concludes, "is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together." Calvino's inferno is much like the state of things in the unnamed city in Jose Saramago's Nobel-winning novel Blindness. The inferno, we might say, makes us blind to our own suffering and inhumanity. Saramago and Fernando Meirelles, who last year adapted Blindness for film, ultimately find reason to hope. Connection among people in intimate, mutually-dependent social networks, they demonstrate, makes life beautiful. Only humanity can humanize. In the voice of Marco Polo, Calvino gives form to the thought. It is Invisible Cities' closing statement. There are two ways to escape suffering [the inferno]. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space. What, in the midst of the inferno, is not inferno? To try to answer such an evocative question, we are compelled to ask this one: What, in the powerful reach of this city's history, can we pull forward, and make endure? The answer may be the city's borrowed Torinese form. As it plans the city's future waterfront, Penn Praxis thinks so. Its plan is predicated on stretching the grid down to the Delaware. There, an authentically intimate Philadelphia can grow. I'd like to think what's not inferno is even more basic to the notion of Philadelphia: the impulse to invent, experiment, create. Penn borrowed the Torinese idea because it fit a new way of thinking about the equality and rights of people. That impulse to experiment wasn't fleeting. It's what made Philadelphia for two and a half centuries a place of almost constant innovation. The trouble today, when we think about making such an impulse endure, is that we find ourselves trapped by the way we've internalized the past. It weighs so much that we're constantly discounting our own ideas. Perhaps this sounds contradictory. Don't we celebrate the richness of our history, so tangible, powerfully alive in the contemporary city? Indeed. Aren't we proud to listen to lost voices? And aren't I, here, doing just that? Indeed. I'd simply like to privilege certain voices over others. At present, there is another reason we've stopped inventing the city. We haven't the space. Each impulse to experiment, invent, create is therefore compromised, often enough neutralized by a need to measure, negotiate, adapt to an existing urban fabric. That, too, you say, is an attribute. Indeed, invention is adaptation. Invention is borrowing, listening, marketing. But it mustn't always be -- not to such an extreme and arduous extent -- or we won't do justice to ourselves, our ideas, our own vision. Do we have the confidence to invent a New Philadelphia?  It was my journey not to Turin, but to Venice, that reminded me we have an ideal location for New Philadelphia. We return to a city trapped by its own past to retrieve our

future. Lewis Mumford is our guide. Venice, he notes, is well-known for its beauty. We all agree to that. But the city was never recognized for its fundamental innovation in

city planning. "The Venetians," he explains, "no doubt inadvertently, invented a new type of city, based on the differentiation and zoning of urban functions."

It was my journey not to Turin, but to Venice, that reminded me we have an ideal location for New Philadelphia. We return to a city trapped by its own past to retrieve our

future. Lewis Mumford is our guide. Venice, he notes, is well-known for its beauty. We all agree to that. But the city was never recognized for its fundamental innovation in

city planning. "The Venetians," he explains, "no doubt inadvertently, invented a new type of city, based on the differentiation and zoning of urban functions." One of the earliest functions was industry. The district of the Arsenal, a shipyard that was Europe's first massive manufacturing center, was first built in 1104. By the 15th century, the shipyard employed 16,000 workers and housed 36,000 seamen. It's an assemblage of long, handsome brick buildings and at least one dry dock, ships, lighthouses, cranes, bridges, empty warehouses, and hidden inlets. In the context of Venice's intimacy, the scale of the Arsenal feels grand. It's the outward-facing industrial redoubt to the inward-facing, intimate center. One kind of space balances, relieves, empowers the other.  At present, with the Biennale exhibits inhabiting much of the Arsenal's available warehouse space (and some of the waterways), visitors are led along endless, sun-baked paths of

crushed limestone. The experience is ameliorated by stools clustered near the entrances of galleries and in groves of trees. These are the lauded "SOS stools" created by

Philadelphia industrial designer Josh Owen. Luminous white in the Venetian light, I take these little innovations as talisman, a timely reminder, for we in Philadelphia have an

Arsenal, a space that would allow us to once again innovate freely.

At present, with the Biennale exhibits inhabiting much of the Arsenal's available warehouse space (and some of the waterways), visitors are led along endless, sun-baked paths of

crushed limestone. The experience is ameliorated by stools clustered near the entrances of galleries and in groves of trees. These are the lauded "SOS stools" created by

Philadelphia industrial designer Josh Owen. Luminous white in the Venetian light, I take these little innovations as talisman, a timely reminder, for we in Philadelphia have an

Arsenal, a space that would allow us to once again innovate freely. That space, indeed, is our Arsenal, the Navy Yard. We'll build New Philadelphia there. To not do so, I argue, is to condemn ourselves to an eternal future of adaptation, and not invention. That's not to say creating a new city at the Navy Yard doesn't require adaptation; it's already a living, magical, visually powerful place. But its power comes in part from its location at the logical base of the city. For whatever reason -- it was a swamp, or already occupied by Swedes or Lenape -- Penn chose a different location for his grid. New Philadelphia allows us then to reclaim the city's first "dead branch," critically at the opposite end of its main axis -- or "trunk" -- from Center City. This is potent planning: old and new Philadelphia not to fight it out, but instead to communicate, relieve, balance one another. (Not an untried approach, particularly by the French, who employed it in their occupied cities of North Africa; it's precisely the idea behind La Defense in Paris and Rem Koolhaus' New Lille.) It's a point, I believe, that the architect Robert A.M. Stern, the Navy Yard's master planner, intrinsically understands. New Philadelphia mustn't copy the old, but rather somehow find way to balance it. So Stern's Navy Yard plan employs broad, curving streets as the apotheosis of the intimate grid. But it does so in the language of suburban development. In other words, Stern passes on the chance to invent, declaring instead he doesn't think us capable of imagining a New Philadelphia. (His official client, the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation, may have had something to do with that.) This is folly, and dangerous. To take a forceful place and turn it into an office park is to give into the inferno. But dare we think differently? Is there any conceivable way to imagine an already struggling city amidst a crippling economic recession finding the kind of resources commensurate with such outsize urges? The last such attempts, during Urban Renewal, were desperately compromised. New Eastwick, the most ambitious of all, was shredded by public outcry, bureaucratic blindness, and rapidly evaporating funding. Wouldn't New Philadelphia, by stealing resources, reduce funding for the rest of the city? Very likely so. The Federal government would have to be convinced this new kind of city is a model for urban development. This administration has already demonstrated a serious interest in urban issues and a sensitivity to Philadelphia as the national crucible. What remains is convincing vision.  New Philadelphia, Calvino might say, shouldn't be a city at all. The Navy Yard is already a place of strange, incongruous magic: its winter palate of ships and steam and bridges and cranes and heavy chains, its water -- everywhere -- its wilds of suburban ruin: all these things like Richard Hayne's anthropological gardens bend time and manipulate reality. Don't mess with it. It's already a trip, man. Once, thousands came here to swim in the dead river. Carve a beach and let them come again. Call in Cristo or Richard Serra: there are miles available here and gray ships like an infinite canvas (let artists do what Tom Chimes and Bruce Nauman say they do best: reveal hidden powers). Scatter Josh Owens' stools and let them sit and marvel. Tastykakes for all. Let them marvel, let them absorb the powerful landscape -- and let them dream. One can't stand at the water's edge, at the edge of the city, and not find oneself at the edge of an idea. The place, alone, compels us to dream. It solicits our most fantastic ideas. Form -- forms -- will follow. They don't quite matter now. In 1916, in Turin, Mattè Trucco took Frederick Winslow Taylor's ideas of scientific management, studied how they were applied by Henry Ford, and invented a new industrial form. At the Fiat Lingotto factory, the assembly of a car would start on the ground floor. Bit by wondrous bit, the car would rise through the factory. Eventually complete, it would emerge in the sky, a wonder of pretense. On the rooftop test track, the car would take a spin then circle down the five story ramp, and out into the expectant world. –Nathaniel Popkin nathaniel.popkin@gmail.com FOR A COMPANION PHOTO ESSAY BY NATHANIEL POPKIN, PLEASE CLICK HERE. For more on The Possible City, please see HERE. For Nathaniel Popkin archives, please see HERE, or visit his web site HERE. |

|

• 26 March 09: Piecing Piers • 7 January 09: Slow Moving, City Alive • 20 November 08: Of weights and visions • 20 October 08: Dreams of a Magic City • 26 September 08: The opposite of decline • 19 September 08: "To see something greater" • 18 September 08: Dwindling/rekindling possibilities • 26 August 08: TPC, NOW AVAILABLE IN PAPERBACK • 26 June 08: The Mother of Invention • 29 Apr 08: "This is not pie-in-the-sky" • 1 Apr 08: Recess/Re-assess • 7 Mar 08: One-City Art Movement, Open to Everyone • 24 Feb 08: Too late for the streetscape? • 15 Feb 08: "It really could be something." • 18 Jan 08: Estuary of Dreams • 11 Jan 08: More than shelter • 10 Jan 08: Nature's balance • 6 Dec 07: Snake uprising • 4 Dec 07: A Junction that ought to be • 6 Nov 07: Around the Mulberry Tree we go • 29 Oct 07: Wondering about wandering • 5 Oct 07: No other way • 21 Sept 07: Here is the Possible City |