11 December 07: The real estate of death:

How many people will Mount Moriah carry in the end?

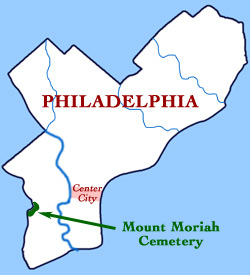

Aw, God said to Abraham "kill me a son." Abe said "man, you must be puttin' me on." God said "no." Abe said "what." God said "you can do what you want Abe, but, the next time you see me comin' you better run." Well Abe said "where do you want this killin' done?" God said "up on Mount Moriah in Jerusalem" -- later and more famously known as the Temple Mount. Abraham's binding of his son Isaac (in preparation of sacrificing him -- out of his fear of God -- which was diverted by an angel) is sacred to and interpreted differently by each of the three major religions. In the tenth century BC, King David envisioned the site as the spiritual center of his burgeoning kingdom of Israel and he instructed his son Solomon to build a temple to serve it. Three thousand years -- and several raids, destructions, reconstructions and more destructions -- later, the site of Solomon's temple is still a pillar to Jews, Christians and Muslims. Though many geographic names hold a religious derivation (Bethlehem and Nazareth, PA, for example), Mount Moriah doesn't seem to be a common one. Two mountains in the US (in New Hampshire and Nevada) and a Missouri village of 143 people share the name Mount Moriah. And, in Southwest Philadelphia up on a hill above Cobbs Creek, Mount Moriah Cemetery is the final resting place of thousands of people.  Mount Moriah Cemetery was incorporated in 1855, one year after the Act of Consolidation folded all boroughs (like Chestnut Hill and Frankford) and townships (like

Northern Liberties and several in the Northeast) under the auspices of a coterminous city-county government. Previously Kingsessing Township, Southwest Philly was

now technically part of the city, but it was still very much a rural, hilly area -- the type of area that was in 19th century vogue for burial grounds, like Laurel

Hill (1836) and Woodlands (1840) before it. However, it wasn't just fashion that begot rural cemeteries; there was the legitimate concern on the handling of dead

bodies in compact, urban places, particularly cities where small, church cemeteries were approaching their finite capacity.

Mount Moriah Cemetery was incorporated in 1855, one year after the Act of Consolidation folded all boroughs (like Chestnut Hill and Frankford) and townships (like

Northern Liberties and several in the Northeast) under the auspices of a coterminous city-county government. Previously Kingsessing Township, Southwest Philly was

now technically part of the city, but it was still very much a rural, hilly area -- the type of area that was in 19th century vogue for burial grounds, like Laurel

Hill (1836) and Woodlands (1840) before it. However, it wasn't just fashion that begot rural cemeteries; there was the legitimate concern on the handling of dead

bodies in compact, urban places, particularly cities where small, church cemeteries were approaching their finite capacity.As the city grew outward and Southwest Philly developed, the trolley followed Kingsessing Avenue (which still borders Mount Moriah Cemetery), allowing people from all over to visit deceased loved ones, or even picnic in the idyllic setting on the hill above Cobbs Creek. This concept may seem unusual or even creepy to us now, but (as this web site mentioned in the Lower Merion/Manayunk open spaces study) this was a common way to pass a Sunday afternoon in the 1800s and even into the 1920s. (There's even a shuttered Cemetery Station between the West Laurel Hill and Westminster Cemeteries in Bala-Cynwyd.) The cemetery itself grew from its original 54 acres to 380 acres across Cobbs Creek in Yeadon, DelCo. (This info, and lots more, is available and excellently maintained by John Ellingsworth at mountmoriahcemetery.org.) But the 1920s were a long time ago, especially in Southwest Philly. Somewhere along the way, it seems that time started forgetting about this cemetery that is the final resting place for Civil War veterans (from both sides of the Mason-Dixon), prominent Philadelphians, and a large contingent of Freemasons. (Masonic iconography is everywhere in Mount Moriah, from the compass symbol to large obelisks, including one in the center of a large circular plot, to the actual masonry in the many tombs.) Though some plots are very well tended, just as many others are not, and are overgrown with weeds, litter, and in some cases, outright dumping. Mount Moriah Cemetery is the sort of place I thought would interest CDoc of The Necessity for Ruins, so I rounded him up down in G-Ho and we headed for the great Southwest to check it out. While we were there, we each wandered in our own direction, meeting up a number of times along the way, once to check out a deserted mausoleum that was missing a door and had become a makeshift depository for used flowers and headstone decorations, and another to engage in conversation with a sharp dressed man who invited us to participate in a ceremony with some of his Masonic brothers, assuring us that "there's nothing secretive about it." (I politely passed, but I can't speak for Chris.) Some other frighteningly harsh observations . . . • In several sections of the Cemetery on the southern end, entire plots have been so overgrown with weeds that the weeds are turning to trees and the trunks are knocking over heavy granite headstones.  All told, Mount Moriah Cemetery is a fascinating place, for reasons good and bad. It's certainly a historic and cherished ground by some accounts, but by others, it doesn't seem a very peaceful final resting place. Depending on how far you're willing to take the thought, it could even venture into the realm of whether permanent physical space is still necessary for the disposal of dead people. Which takes us back to the beginning of this piece, varying religious outlooks on the same subject, be it the historical significance of Jerusalem's Mount Moriah or what to do with a human corpse. Not everyone agrees with cremation. (I suppose I would prefer being cremated, but only after science has taken all it needs . . . I doubt it will have much use for my liver, for example.) Mummification is pretty impractical by modern standards. Cannibalism is generally frowned upon. Cremation aside, that leaves us pretty much with burial. With over 6 billion people in the world, let's estimate that half of them will be buried . . . that's over three billion plots of the earth that will be populated by wooden boxes with corpses in them. Whether they truly rest in peace is up to the generations after them. There's legal perpetuity, as Mount Moriah has and which prevented the construction of a Cobbs Creek Expressway (I-695) in the 1950s, but even that can be overturned by the right politician's signature. (We've all seen Poltergeist, although honestly, what were they doing staying in the house the night after an exorcism, other than to parade JoBeth Williams around in her underwear? Duh.) What was it the big man said? In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes. That's the one. Guess we should pick out our place while there's still a place to pick.  –B Love |