|

|

|

15 July 08: Philly Skyline vs Penny Postcards:

Of height, history and precedence

William Penn's "green country towne" (or "greene countrie towne" or "green country town", however you wish to spell it) ceased being a green country towne at

just about the moment he left town in 1701. Penn pictured an idyllic town of houses centered on lots surrounded by gardens and trees, but Philadelphia was still

very much the (relatively) bustling seat of his colony whose other townships stretched well north, south and west along the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers.

While many early settlers were like Penn Quakers, Europeans of Presbyterian, Anglican and other denominations from England, Germany, Ireland, Scotland and the

Netherlands also took Penn up on his holy experiment. As did, of course, those of the entrepreneurial spirit.

Philadelphia was already a bona fide city, the largest in the colonies, when Peter Cooper painted his "South East Prospect of the City of Philadelphia", the

oldest existing painting of an American city. (You can view the original at the Library Company, on whose web site the header includes a reproduction of this.) The growing city centered itself around the port on what is now . . . Penn's Landing.

Christ Church's congregation grew faster than the other early colonial churches, enough to warrant the construction of a new church on 2nd Street just above

High (Market) Street. Built between 1727 and 1744 on John Kearsley's design (itself modeled on the English style of Sir Christopher Wren), Christ Church was

always intended to have a grand steeple, but it took two lotteries -- there was no real fundraising at the time -- led by a congregation member whose

wife was a far more active attendee, and this task would do well for his absentee reputation. They called him Benjamin Franklin.

Franklin's second lottery concluded in 1752, and over the next two years, a wooden steeple designed by Robert Smith -- a Scotsman who many consider the foremost

architect of colonial America and who is also responsible for Carpenters Hall and St Peter's Church at 3rd & Pine -- was built to a height of 199', where a

gilded crown symbolizing the British Empire reigned. Legend has it that the crown was prophetically destroyed by lightning in 1776; the weather vane and

bishop's mitre that still adorn the steeple were placed there in 1787. (1)

Franklin's second lottery concluded in 1752, and over the next two years, a wooden steeple designed by Robert Smith -- a Scotsman who many consider the foremost

architect of colonial America and who is also responsible for Carpenters Hall and St Peter's Church at 3rd & Pine -- was built to a height of 199', where a

gilded crown symbolizing the British Empire reigned. Legend has it that the crown was prophetically destroyed by lightning in 1776; the weather vane and

bishop's mitre that still adorn the steeple were placed there in 1787. (1)

Speaking of infamous lightning strikes, the Christ Church Preservation Trust's executive director Don Smith has a theory about Franklin's kite experiment.

"Franklin had written his lightning rod theory [in 1750] and wanted to test it out on the steeple, but he got bored waiting for it to be built and went out with

his son [in 1752, when construction had only begun] with his kite."

"It's just a theory," Smith laughs . . . but it's a good one. He also relates another tale that sees a drunken John Adams climbing the stairs of the steeple to

get away from the stank, obnoxious streets below to gaze out over the city.

A more solid fact that he and his Christ Church brethren are quick to share is that building's reign as the tallest in colonial America. From its completion in

1754, through 1810, when a very similar-looking Park Street Church was built in Boston 18 feet taller, Christ Church was the tallest building in America, a

period of 56 years. For some modern perspective, no building since has had so long a reign, the Empire State Building coming closest at 41 years from 1931 to

1972, when the World Trade Center eclipsed it, itself only lasting two years before Sears Tower topped it.

The significance of Christ Church's steeple was not lost on artist George Heap, who answered the call of Thomas Penn (William's son) in 1750 to depict a more

modern view of Philadelphia than Cooper's thirty years prior. However, as the steeple was not yet finished, he had to use Smith's drawings to include it in his

East Prospect of the City of Philadelphia, what might be considered the first ever view of the Philly Skyline. The resulting engraving, which Heap never

saw -- he died on the ship to England where it was to be engraved, and his co-publisher Nicholas Scull finished the task -- had several printings, the oldest of

which is at the Library of Congress. (2) There are also copies at Christ Church

and the Philosophical Society.

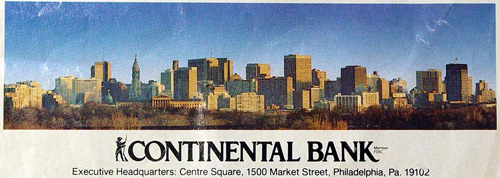

Cooper's and Heap's Philly Skylines must have been inspiration for P. Sanders, whose 'art series' postcards were prevalent in the very early 1900s, including

the "Harbor Scene and Sky Line" pictured at the beginning of this post. In it, Christ Church and City Hall dominate the low-lying industrial city.

What an amazing time post-Civil War Philadelphia must have been; industry and art conducted the city. The workshop of the world; Baldwin, Stetson, Eakins,

Wanamaker, Furness. The city's growth moved the center of gravity to the Centre Square, the one Penn had set aside long ago for civic buildings. Now able to

justify such a civic edifice, the city established a committee for the sole purpose of crafting a new building to occupy Centre Square, moving the city's

government from Independence Square. The committee and winning architect John McArthur not only agreed on the complexly flamboyant French Second Empire building

(adorned by Alexander Milne Calder's sculpture) we see today, but in their 1871 world of civic pride, they wanted their new city temple to be the tallest in the

world -- 511' to the top, with a 37' statue of the Quaker founder on top.

What an amazing time post-Civil War Philadelphia must have been; industry and art conducted the city. The workshop of the world; Baldwin, Stetson, Eakins,

Wanamaker, Furness. The city's growth moved the center of gravity to the Centre Square, the one Penn had set aside long ago for civic buildings. Now able to

justify such a civic edifice, the city established a committee for the sole purpose of crafting a new building to occupy Centre Square, moving the city's

government from Independence Square. The committee and winning architect John McArthur not only agreed on the complexly flamboyant French Second Empire building

(adorned by Alexander Milne Calder's sculpture) we see today, but in their 1871 world of civic pride, they wanted their new city temple to be the tallest in the

world -- 511' to the top, with a 37' statue of the Quaker founder on top.

City Hall tour director Greta Greenberger has lived and breathed (in) that building for the better part of two decades. "We were really gutsy . . . not just

because it was a height no one had seen, but because of how conservative [in the Quaker sense] Philadelphia was," she says of City Hall's ambitious plans. "Of

course," she continues, "by the time it opened, it was old news."

It took thirty years for McArthur's vision to come about, and in that timeframe, both the Washington Monument (1884, 555') and the Eiffel Tower (1889, 984')

stole City Hall's thunder. Even in 1901, it begged the question asked of skyscrapers today: what criteria measures height? Structural? Architectural? Roofline?

Burj Dubai will -- at least for a little while -- lay to rest any controversy of height measurements, as its completed height in the neighborhood of 2,700'

annihilates the figures of Toronto's CN Tower (1,815' structural height), Taipei 101 (1,671' architectural/spire height), and Chicago's Sears Tower (1,454' roof

height).

When City Hall ground was broken at Centre Square in 1871, the tallest building in the world was the Houses of Parliament in London, at 335'. (Unless you count

the Great Pyramid of Giza, which is fair, and which is 481'.) When City Hall opened in 1901, twenty-two buildings were taller than London's palace. (3)

It's worth noting here that the Centennial

Tower, a 1,000' observation deck proposed for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Fairmount Park, was never built. (Perhaps it's also worth noting that Philly

Skyline would like to see the World's Tallest Flagpole in its place.)

In spite of being surpassed in 1884 by the 555' Washington Monument and in 1889 by the 984' Eiffel Tower, City Hall's colossal 30 years of construction at very

least could award itself the tallest occupiable building in the world . . . for seven years, as New York's Singer Tower bested it at 612'. (An interesting aside

about that building: it is the tallest building to ever have been commissioned for demolition -- demolished in the 60s for what is now known as Liberty Plaza --

as opposed to the WTC, whose destruction was obviously a consequence of tragedy/cowardice.) Still today, City Hall is the tallest load bearing masonry building

in the world.

In yet another twist around City Hall's 30 year construction, the simultaneous development of the steel structural frame in Chicago and the standardization of

elevators effectively guaranteed City Hall's distinction atop that masonry category, as the steel frame accelerated construction, created a lighter building,

and increased floor space. When Chicago hosted the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, it was well stocked with skyscrapers and architecture that would be a

focal point of the exposition, which was largely about the city. That city's affection for building high has spanned, and continues to span, generations

of styles from the Monadnock Building to the Wrigley Building to the Sears Tower and John Hancock Center to the Chicago Spire, the 2,000' twisting tower under

construction now.

Philadelphia didn't have reason to build a skyline to mark the center of a region like Chicago, what with that other skyscraper city 90 miles north. But if City

Hall is any evidence, we weren't some podunk town, either. A small handful of buildings like the Stephen Girard Building (1896, 12th & Ludlow), North American

Building (1900, Broad & Walnut), Land Title Building (1897, by Chicago's Daniel Burnham), and the Franklin Bank (1889) and Betz (1892) Buildings (those two

buildings stood adjacently where the PNB Building now stands) were already completed nearby to welcome the completion of City Hall onto Philly's turn of the

20th century skyline.

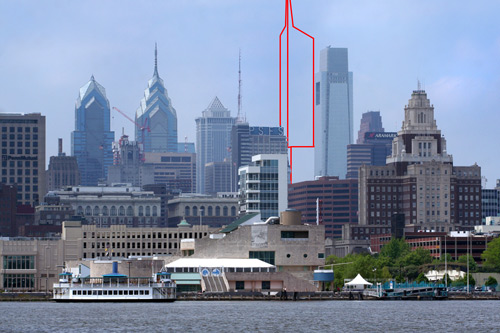

It was shortly after that turn of the 20th century that P Sanders printed his postcard of the "Harbor Scene and Sky Line". Fast forward a full century, and that

familiar riverfront scene looks like this:

Christ Church, once the colonies' tallest building, and City Hall, once the world's tallest occupiable building, are now hemmed in by neighbors new and newer.

Perhaps the only one of them that had the same sort of impact either of them had was One Liberty Place, itself now looking up to someone else.

When One Liberty Place opened in 1987, it was the 12th tallest building in the world. The more notable, and notorious, achievement though, was of course its

height of 945' (or 960', depending on which printed figure you choose to go by), shattering the long lived reign of William Penn atop City Hall and atop

Philadelphia.

When the gentleman's agreement came to be is anyone's guess. I've not seen it documented and my search to find it has proven fruitless. Ed Bacon is usually

credited -- blamed? -- for enforcing such a thing when 1950s urban renewal gave the city its first growth spurt since the PSFS Building capped off the 20s & 30s

with its own signature. The 50s, 60s and 70s saw a lot of flat top boxes dull out the skyline. The once majestic view from the Art Museum was dumbed down by

four dominating Park Towne Place towers and leveled off in the distance by modernist and brutalist buildings which, on their own, are deserving of merit, but

banded together did nothing more for the skyline than create a Pennsylvania Flat Top Box.

One Liberty Place, currently the 51st tallest building in the world, helped -- insisted -- this city emerge from this gentleman's agreement silliness in

the 1980s. While there is no accounting for taste -- some people absolutely love One Liberty and what it represents, others cast it off as nothing more than an

ersatz Chrysler Building -- there's no denying that it and its peers of the 80s and 90s redefined the Philly Skyline, and in turn rejuvenated our

interpretations of everything that skylines do: make first impressions when entering a city, marking the center of the region they represent, provide material

for photographers and graphic designers to identify place.

After a decade or so in this mold, Cira Centre updated that update by bringing the skyline across the Schuylkill, and modest, mid-sized towers like the St

James, Symphony House and Murano have added a little more bulk. Comcast Center, whose construction this web site covered

obsessively, is an impressive 975' -- colossal by Philly standards and 43rd tallest in the world -- but as the skyline goes, it did little more than to fill

a gap between the Bell Atlantic Tower and Mellon Bank Center, stately though it may be. Comcast did not have the impact One Liberty Place clearly did two

decades earlier. The biggest buzz Comcast has generated, appropriately enough, comes from the massive HDTV in its lobby. The tower, as Inga Saffron illustrated

in her review, honors Brian Roberts' wishes to keep it modest and elegant. And while it's clearly the tallest thing on the skyline, as seen from familiar places

like the eastbound Schuylkill Expressway coming around the turn at Girard Ave, or Belmont Plateau, or the stadium complex, it doesn't pack the wow factor

something like, oh, this thing would:

Since yr Philly Skyline broke the ACC story, a whirlwind of information, right and wrong, has permeated the

local media. With it, the predictable opposition and typical pessimistic reaction have mounted. But, ACC has also gained quite a bit of support, not just from

Mayor Nutter and Deputy Mayor Altman, but also from generally warm receptions by the Logan Square Neighborhood Association and the Planning Commission, who

today is holding their first official hearing on the project. May's presentation was an information-only icebreaker, a step encouraged by the Mayor's push for

Planning strength and a commitment by the developer, Walnut Street Capital for transparency. Really, to this point, the only opposition that's gotten any

attention is that by a small group of tenants at the Kennedy House who claim the building is out of scale . . . at 18th & Arch . . . in the very heart of the

city's business district . . . and from lame duck state senator Vince Fumo, who . . . I'm not really sure what his beef is, but I'll bet it has something to do

with the 125' height restriction overlay he got Councilman Darrell Clarke to write in response to the Barnes Tower / Parkway 22, which so far has been nothing

more than minor demolition on Spring Garden Street and some Flash ads on philly.com. Councilman Clarke was so beholden to his own legislation that he introduced

legislation that would change the site's zoning to allow for ACC's construction at 12 times the height limit he set only a year ago.

Morton Silverman, president of the Kennedy House's resident association, circulated a letter to fellow tenants and neighbors hoping to "organize opposition to

the 'tallest building in the world' as soon as possible." It's not the tallest building in the world, nor even the US. The letter issues to "protect ourselves

from being permanently draped in shadows and swamped with traffic associated with filling its outlandish 63 floors." Considering Kennedy House is a block

southwest of ACC and that the sun shines from the south for most of the year, Kennedy House will be in shadows for at most an hour in the very early morning,

for a couple weeks around the summer solstice.

As for traffic? Considering ACC is at 18th & Arch, it has easy access to every regional rail and trolley line in the city, as well as the el and subway.

Considering ACC is aiming for LEED gold-or-higher certification, using transit is strongly encouraged, not to mention the bike racks that will be installed, not

to mention gas prices and where they will be by ACC's completion.

So there's your primary opposition . . . from an outgoing senator who's awaiting trial for 139 counts of corruption and who called a colleague a "faggot" on the

senate floor, and from a group of people living in a highrise in an "urban village" that coincides with the central business district. It's not much opposition

at all, really. So little, in fact, that support for ACC ought to get as much a shake as the usual Negadelphian squeaky wheels.

For example? If the amount of email I've received following ACC is not enough indication, take LSN4ACC, or,

Logan Square Neighbors for American Commerce Center. Started by Mark Flood and Chris Paliani, who happen to live on the north side of the street where ACC is

planned, which is to say they will be in its shadows, LSN4ACC is a grass roots organization who "appreciate[s] good design, good architecture, good urban

planning, and historic preservation. We recognize that world class cities need jobs and great buildings -- not surface parking."

For example? If the amount of email I've received following ACC is not enough indication, take LSN4ACC, or,

Logan Square Neighbors for American Commerce Center. Started by Mark Flood and Chris Paliani, who happen to live on the north side of the street where ACC is

planned, which is to say they will be in its shadows, LSN4ACC is a grass roots organization who "appreciate[s] good design, good architecture, good urban

planning, and historic preservation. We recognize that world class cities need jobs and great buildings -- not surface parking."

Flood elaborates, "it's going to be LEED Gold certified, which is the kind of responsible and sustainable development we need to be supporting. The

neighborhood is looking for more retail and the building responds with amenities like restaurants, a supermarket and a theater. Plus, it's designed by a

world-class architect and it's beautiful. This is a real asset to our neighborhood and our city."

And I agree, wholeheartedly. If it hasn't come through in previous writings, I firmly support the concept of American Commerce Center. So does Nathaniel Popkin.

So does Steve Ives. So do Michelle Schmitt and Matt Johnson. It stands to reason that a Philly Skyline is pro-something that would alter the skyline.

But, ACC does much more than add a new building to the skyline. It sets the green building benchmark I think the city needs if it truly wishes to embrace

sustainability, much more so than Comcast Center, and where the Convention Center dropped the ball. Ever importantly, it welcomes its place on the street, along

18th with open space, along Arch with retail, at 19th with a chamfered corner for office workers, and on multiple levels with public park space. It packs the

wow factor that One Liberty Place did, and which City Hall and Christ Church once did.

The height precedent is there (Christ Church and City Hall were the tallest buildings in the US in their day -- ACC would only be third, and height dimensions

are simply arbitrary given the technology of our day). It's like I said on CBS3: Philadelphia rightfully celebrates its history and always should. But, that

doesn't mean we should be stuck in it. We need to keep creating history, setting and reaching goals that years from now we'll consider 21st century history. By

then, something bigger and better could be here, but it could very well thank ACC for its chance to be there.

ACC can take the torch of Philadelphia's landmarks: Christ Church, monument to faith, once the tallest building in the US. City Hall, monument to civic pride

and civic rule, once the tallest (habitable) building in the US. Even King of Prussia Mall, monument to retail and the suburban lifestyle, once the largest mall

in the US. Now, American Commerce Center: monument to sustainability and technology, tallest building in the city and one of the tallest in the country. Why

not?

HERE.

NOTES & SOURCES:

1. The Building of Christ Church, by Charles E. Peterson, 1981, referenced at christchurchphila.org.

2. Legacies of Genius: A Celebration of Philadelphia Libraries, edited by Edwin Wolf, 1988.

3. Skyscraperpage Diagrams

Additional info:

• Philadelphia Architecture: A Guide to the City, edited by John Andrew Gallery and published by the Foundation for Architecture, 1994.

• "An East Prospect of the City of Philadelphia", by George Heap from the Camden riverfront, under the direction of Nicholas Scull, surveyor general of

the province of Pennsylvania. Engraved and published according to an act of British Parliament by Gerard Vandergucht: 1753, 1756, 1768.

• "Continental Bank" ad accessed at Philadelphia Central Library's print department, originally run in 1984.

• Christ Church steeple illustration courtesy of Don Smith, Christ Church Preservation Trust

• "Harbor Scene and Sky Line" postcard published by P. Sander, Philadelphia & Atlantic City, for Sander's Art Series

• Postcard was not mailed

• Contemporary photo taken by B Love, 5 May 08

PREVIOUSLY ON PHILLY SKYLINE VS PENNY POSTCARDS:

6 May 08: The FDR Park Gazebo

17 April 08: Walnut Lane Bridge

18 March 08: The Parkway & the Skyline

10 March 08: 1800 Arch Street

27 February 08: New Market

7 March 07: Letitia Street House

–B Love

|

|

|