20 November 08: The Possible City

Of Weights and Visions

by Nathaniel Popkin November 20, 2008 Sometime in the 1840s, and only in his twenties, and sporting a head of long hair and thick sideburns, and a velvet collar, the radical author George Lippard looked up at the silver sky and saw a Paris, glimmering and ghastly. The glare of many lights flashed out upon the winter night. Above, the clear cold sky of a calm winter twilight overarched the far extending perspective, brilliant with light and life, which marked the extent and grandeur of that wide street of a gorgeous city.Could this be Chestnut Street? Looking carefully, he "beheld the sidewalks lined with throngs of wayfarers, some clad in purple and fine linen, some with rags fluttering around their wasted forms. Here was the lady in all the glitter of her plumes, and silks, and diamonds, and by her side the beggar child . . ." Lippard wrote the vision as a chapter, "Devil-Bug's Dream," in his best-selling novel The Quaker City. Here was Philadelphia, a century on, in 1950, as ugly and beautiful as the Paris Ben Franklin had entered in 1776. A white marble palace, under construction, occupied Independence Square. In the foreground, Independence Hall, "a small and unpretending structure of brick," appeared as a tiny ruin. "In the year eighteen forty-two," wondered Devil-Bug, "there was some fuss about a monument to Gin'ral Washington, in Washington Square -- can you tell me, stranger, whatever became of it?" In this 1950, a massive jail and gallows sat atop Washington Square. Sometime in 1959, Philadelphia's planning director Ed Bacon looked out across the symmetrical gardens that now framed Independence Hall, and he saw emerging "the most interesting and beautiful center city in the country." Bacon's gleaming vision, "Philadelphia in the Year 2009," published in the October, 1959 Greater Philadelphia Magazine, revealed a city poised for pleasure. Here, Philadelphia had seized an opportunity, the 1976 Bicentennial, in order to complete a transformation, from dirty industrial metropolis to satisfying playground. But the great attraction will be the open-sided electric cars with their striped awnings that go up and down the length of Chestnut Street, which has been relieved of automobiles to provide enough room for the visitors to the Fair. Chestnut Street is the backbone of the Fair . . . the Midway where the visitors spend their money for food, drinks, mementos and all the various necessities and frivolities that go with such an event . . .Bacon's vision emerged at the height of the Cold War, when the United States sought to demonstrate the sustained power of its ideals. What better way, thought the city planner, than to demonstrate American vitality and relevance to the world than to stage a world's fair amidst its brilliantly reconstructed original city? "In this way the reconsideration of the ideas of 1776 will occur in the place where they were originally formulated," he explained, seeking confluence where Lippard found bitter irony. His Washington Square prison was full of "the brave men who struck the last blow for the liberty of the land, against the tyranny of the new-risen nobility." Lippard, who sometimes wrote like a Marxist, as Marx was coincidentally doing, may have found himself on the wrong side of the Cold War. Both loved -- and must have been deeply, infuriatingly, disappointed by -- Philadelphia. Lippard came to Philadelphia during the depression of 1837, encountered unimaginable poverty and then a few years later saw an economy booming quite literally on the backs of the poor. Devil-Bug's 1950 must have seemed a certain reality. Having been so successful advancing his vision in the 1950s, Bacon, for his part, imagined the Bicentennial would be enough to convince the federal government to make Philadelphia its bona fide urban jewel ("the key prestige city in the country"), and that the infrastructure build-up to 1976 would stimulate the farthest-reaching transformation. Perhaps he thought that prospect would guarantee a continuation of the progressive and careful leadership the city was then enjoying, leadership that would propel the city beyond the Bicentennial to "the year 2009 [when] no part of Philadelphia is ugly or depressed." * * * Completing that last exhalation, Bacon wrote, "Of course I actually know no more about Philadelphia in 2009 than does anyone else." "I have tried to show, however, by looking backward, that a strong idea has a life of its own, and become a dominant factor if it is clear enough, and if the leadership is stimulated to action."  It may be that Bacon suffered the pre-race riot, pre-suburbanization, pre-deindustrialization, pre-Vietnam, pre-Reagan hubris of the modern city planner; he couldn't have

quite seen what was coming. And yet despite this, many of his ideas persist, and some of his projections for 2009 are part of the present reality: among them, a unified

regional transit system, the Schuylkill Banks, the formation and growth of University City, the residential development and expansion of Center City, the elaboration of

Independence Mall, the emergence of the hospitality industry, the invigorating effect of the sidewalk café.

It may be that Bacon suffered the pre-race riot, pre-suburbanization, pre-deindustrialization, pre-Vietnam, pre-Reagan hubris of the modern city planner; he couldn't have

quite seen what was coming. And yet despite this, many of his ideas persist, and some of his projections for 2009 are part of the present reality: among them, a unified

regional transit system, the Schuylkill Banks, the formation and growth of University City, the residential development and expansion of Center City, the elaboration of

Independence Mall, the emergence of the hospitality industry, the invigorating effect of the sidewalk café.Bacon in 1959 would not have imagined the present scale of adaptive reuse -- factories and mills and firehouses and churches, garages and rowhouses and storefronts retrofitted and re-commissioned for us, today. He wouldn't have guessed the depth and breadth of art-making, the growth of major institutions, the range and sport of cuisine. Nor could he have imagined Philadelphia with nearly 600,000 fewer residents, the result of which -- so many devastated, wasted Ridge Avenues -- makes the 1950s term "blight" sound quaint, like "senile" to describe someone with Alzheimer's. Still, from 1959, he would have equated our politics with the landscape of his own period. Joseph Clark and Richardson Dilworth, the mayors he served during the 1950s, aimed to professionalize and reform, and elevated city planning above parochialism. There is another way that Bacon's imagined path to 2009 informs our own quest for a greater city: the hot breath of opportunity. Said Bacon of the Bicentennial, "It will bring about acceptance of many ideas not otherwise acceptable, and accomplishment of many specific things that otherwise would not get done." We might say the same of President-elect Barack Obama's response to economic and fiscal crisis. In a telling break from the past several administrations, Obama has long promised a White House office on cities and a national infrastructure bank. Now, it seems likely that investment in the nation's troubled infrastructure will become a locus for revamping the economy, not only to help the nation grow again, but as a mechanism of environmental sustainability. If that's the case, like many old cities hoping to benefit, Philadelphia had better be prepared. But how should it direct such investment -- to fix the current physical plant, or to implement ideas for the city of the future? To shore up housing or roads or transit or ports, parks or waterfronts or airports or sidewalks, green roofs or insulation, architecture, or perhaps, demolition? The answer will depend, in the first part, on vision. Let Mayor Nutter ask his favorite question, "What kind of city do we want to be?" and a direction, or several competing directions, may emerge. Among the possible directions, using a broad brush, I turn to these two:  The Delaware Waterfront. The river, and all its concomitant and pluralistic advantages, still sits there, 23 miles long, underused and

disconnected. It's costing us everything. I speak of opportunity cost, of the wealth and vibrancy not now generated. We can no longer afford to let it pass by.

The Delaware Waterfront. The river, and all its concomitant and pluralistic advantages, still sits there, 23 miles long, underused and

disconnected. It's costing us everything. I speak of opportunity cost, of the wealth and vibrancy not now generated. We can no longer afford to let it pass by.Only major action -- the epic investment that might emerge from the Obama program and which was articulated, defined, and wisely evaluated by Harris Steinberg and Penn Praxis -- can piece it together (or properly separate uses, when necessary) and weave it back into the fabric of the city. By doing so, Philadelphia will be forced to consider the growth of the port -- improving its function as a multi-modal hub and weighing the vagaries and advantages of dredging -- alongside recreation, alongside retail and residential projects, alongside wetlands, trails, and nature preserves, alongside the Navy Yard, that most telling unfulfilled resource. Here is an opportunity to expand high-speed transit where it is badly needed and connect now disparate places; an opportunity to use vessels to move people, to delight them, to put them in touch with the river. Neighborhood Preservation. Allowing our rowhouses to suffer from deferred maintenance is costing us, and that too is something we can no longer afford. As block after block declines, we waste materials and architecture, history and tradition -- and we waste energy. In some parts of North Philadelphia especially, the loss is overwhelming. It clearly surpasses the rate of population decline (much in the way the opposite is true: in suburban areas the rate of sprawl far outweighs the growth of population). The result is ugliness and danger and also vast inefficiencies in the distribution of government service. SEPTA works better, for example, in the densest parts of the city. Depopulation is simply wasteful. But it continues essentially unabated. Should cities play a role in a new green revolution, while it's still possible, we need a mechanism to preserve streets and neighborhoods. Here's one: fund homeowners to insulate and weatherproof their row homes, install energy efficient windows, fix structural inadequacies, and preserve original materials and details. If a homeowner can afford the utility bill, she will stay longer, and in so doing assert much-needed stability. If applied right and funded fully, the results will be far-reaching. Imagine shrinking Philadelphia's carbon footprint by properly insulating and weather-proofing 200,000 row homes, half of the city's stock. Just the work alone will sustain a constellation of small contractors. Now let's invent a way to capture lost architectural elements, restore them, and make them available to the rest of the city. Now let's create new kinds of historic districts as a way to leverage and highlight what's special about Frankford, say, or Nicetown. The vision part, I think you'll agree, is relatively easy to form. I've provided but two ideas. In five minutes my in-box could be filled with dozens more. The other part -- what must have tormented Bacon at the end -- political will, fortune, and capacity, is unfortunately a matter of another recurring Philadelphia story. * * * Ed Bacon began his 1959 article by searching for the modern origins of his ideas and in doing so looked back 50 years to 1909, at the start of the Parkway project. For our purposes, we'll retract the gaze slightly to the end of 1911, and the election of Rudolph Blankenburg as mayor. Blankenburg, an immigrant born in 1843 (as Lippard was writing The Quaker City) near Hanover, Germany, was a great Santa Claus of a man, known as the "Old War Horse of Reform." According to the New York Times, "his election in 1911 was the climax of one of the greatest reform campaigns ever fought in this country," as it ended, at least temporarily, the hold of the Republican machine already 40 years in power (the next to do so would be Joseph Clark, in 1952).  The same day Philadelphians surprised the nation by electing a progressive reformer (his Republican enemies jeeringly called Blankenburg a "socialist"), voters granted

the city the power to borrow an unlimited amount of capital to build new subways and to improve the port. Blankenburg rose to power with a mandate: to end the parochial

intransigence. He immediately fired political hacks, instituted civil service rules, and hired leading planners, technocrats, and engineers. Among them was A. Merritt

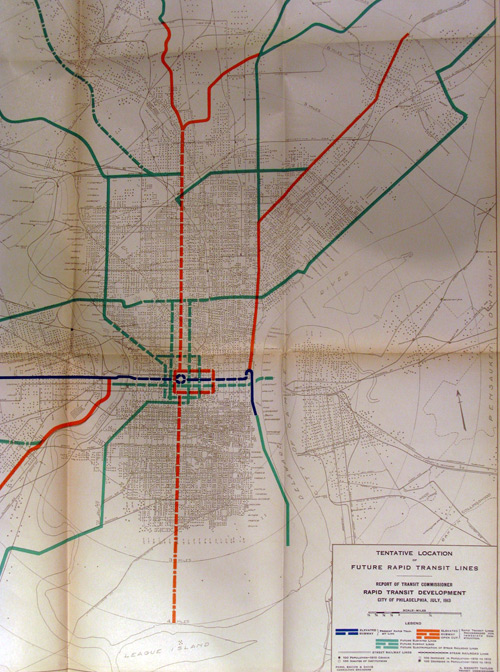

Taylor, a New Jersey railroad executive and planner, who had already begun a Philadelphia transit plan. By the spring of 1912, after methodically analyzing Philadelphia

population density and range of travel (for 5¢ , 8¢ , and 10¢ ) and having listened to localized opposition (the church leaders along Lehigh Avenue were

opposed to an elevated there), and the mayor himself (who insisted on a downtown loop to serve retail and theatre), Taylor's map had fully evolved: now Philadelphia's

system, as those in New York and Chicago, would capture -- and amplify -- the emerging urban energy.

The same day Philadelphians surprised the nation by electing a progressive reformer (his Republican enemies jeeringly called Blankenburg a "socialist"), voters granted

the city the power to borrow an unlimited amount of capital to build new subways and to improve the port. Blankenburg rose to power with a mandate: to end the parochial

intransigence. He immediately fired political hacks, instituted civil service rules, and hired leading planners, technocrats, and engineers. Among them was A. Merritt

Taylor, a New Jersey railroad executive and planner, who had already begun a Philadelphia transit plan. By the spring of 1912, after methodically analyzing Philadelphia

population density and range of travel (for 5¢ , 8¢ , and 10¢ ) and having listened to localized opposition (the church leaders along Lehigh Avenue were

opposed to an elevated there), and the mayor himself (who insisted on a downtown loop to serve retail and theatre), Taylor's map had fully evolved: now Philadelphia's

system, as those in New York and Chicago, would capture -- and amplify -- the emerging urban energy."The plan," according to Michael Krasulski, a Philadelphia University collections librarian, "was not to service what the city was, but what they imagined the city would become." That imagined city's skeleton was formed by a combined subway and elevated system on Market Street (already then in place), Broad, Front Street and Richmond Street (north and south along the waterfront), Kensington and Frankford Avenues, West Passyunk and 28th Street in South Philadelphia, the Parkway and up 29th Street in North Philadelphia, Allegheny, Henry, and ultimately Germantown Avenues, Chestnut Street, Locust, and Arch in Center City, Baltimore (altered to Woodland), Lancaster, and Haverford Avenues in West Philadelphia. Krasulski, who was kind enough to share his own complete collection of "Reports of the Transit Commissioners," richly detailed bound volumes discarded by the Harvard University Library, had for a while kept a website of this imagined system. Imagined, indeed. Despite access to unlimited capital, despite the amplified role of professionals, despite a mayor whose singular insistence pushed the plan forward, despite bids in spring, 1912 to begin construction on the system's backbone, the Broad Street subway, by early 1915 nothing had happened. On January 14, thousands of Navy Yard workers marched on Broad Street to a protest meeting they had organized at the Academy of Music. They demanded that construction start immediately. A Navy Yard employee by the name of Archie Allen offered a resolution, then ratified, which began: Whereas the people of Philadelphia are suffering intolerable hardships, and the future development of the city is imperiled . . . The city of Philadelphia is now legally qualified, financially able, and properly equipped to proceed with the construction of the high-speed transit system . . .On September 11, 1915, Mayor Blankenburg "turned the first spadeful of earth" for the Broad Street subway. The Frankford elevated was also underway. But little actually happened on Broad Street; with war looming, the city sealed the excavation -- until 1924. The South Broad portion of the subway wasn't open until 1930, and that only to Lombard-South. It never reached the Navy Yard, an error we should not at present ignore.  Click to enlarge 1913 transit plan. Little else -- the Ridge spur, the Locust Street subway, the Front Street El south to South Street -- of Taylor's plan was ever built. And even some of that has disappeared. * * * While other cities are quick to see the benefits to be derived from all the varieties of improvement, and rapid in their adoption, here in Philadelphia progressive men are compelled to coax and struggle with a mass of inert and sleepy citizens, who don't wish to have their time-worn notions disturbed. Strange to say, some of the stubborn class who visit other and "faster" towns are among the loudest in complaint of our want of spirit on their return; yet they are seldom more inclined to put their shoulders to the wheel to help us along than they were before they traveled.The weary progressive, poor fellow. He -- she -- emerges every generation, only to meet the "drag-weights;" only to compromise endlessly, and put up with constant failure. "Our Drag-Weights" is the title of an unsigned editorial in the January 28, 1858 Evening Journal, from which the above passage is taken. The late 1850s, as the late 1950s, felt like an era of delicious promise. The Pennsylvania Railroad was finally completed, around the Horseshoe Curve and across the Alleghenies to Pittsburgh, in 1854. The city consolidated its border districts the same year. There was intensifying talk of a new City Hall, to meet the needs of a professionalizing government, and of a vast city park, one that would exceed New York's Central Park, just then under construction. And yet, would any of these ambitious, visionary, and necessary things ever happen? It had begun to feel like they wouldn't. Anti-urban Harrisburg wasn't too interested, but that was only one drag-weight. The rest was corruption, in-fighting, parochialism, and ambivalence, and so both projects stalled -- all this intransigence despite the city's status -- still preeminent in engineering, technology, science, its vast wealth under-pinning much of the nation's growth. The Evening Journal continued, Yes, let the truth be flatly told -- we are slow. Miles of houses, and six hundred thousand inhabitants, are grand things to contemplate; but, in our case, they only render our laggard spirit more conspicuous . . . .We are slow -- we are provincial -- and we must shake off the sluggish influence of Pennsylvania Conestogaism, and rouse the class who are now mere drag-weights to an active sympathy and co-operation with our public-spirited men, or we shall never attain the rank of a genuine metropolis, even if we spread our houses over a wide a space as that occupied by London.Today, a different nation, a world of cities measured not so much by London as by Shanghai and São Paulo. If Philadelphia is to pull off any portion of the infrastructure plan I mention here, or another, and seize the brilliant opening, it can no longer rely on status. It has little standing. It -- we -- can't afford drag-weights, for too much is already stacked against us. Let's not deceive ourselves as perhaps Ed Bacon did, in 1959. Americans don't care about the vitality of the nation's birthplace; they see no particular advantage to preserving it. The impetus to make the Delaware work for us again, to serve our needs while regaining a sense of its own nature, the force by which we stem the apocalyptic scale of neighborhood decline and put an end to demolition by neglect, these things are really up to us. "When," asked the men of the Evening Journal, "shall we exhibit an energy commensurate with our size and resources?" –Nathaniel Popkin nathaniel.popkin@gmail.com For more on The Possible City, please see HERE. For Nathaniel Popkin archives, please see HERE, or visit his web site HERE. NOTE: the author thanks Rob Armstrong of the Fairmount Park Commission, Scott Knowles, director of the Great Works Symposium at Drexel University and editor of the forthcoming Philadelphia in the Year 2009 (Penn Press, 2009), and Michael Krasulski, architecture and art collections librarian at Philadelphia University for lending the materials from which this essay is derived. For more information on Mayor Blankenburg's infrastructure plan, see The Necessity For Ruins' March 2007 archive HERE. |

|

• 20 October 08: Dreams of a Magic City • 26 September 08: The opposite of decline • 19 September 08: "To see something greater" • 18 September 08: Dwindling/rekindling possibilities • 26 August 08: TPC, NOW AVAILABLE IN PAPERBACK • 26 June 08: The Mother of Invention • 29 Apr 08: "This is not pie-in-the-sky" • 1 Apr 08: Recess/Re-assess • 7 Mar 08: One-City Art Movement, Open to Everyone • 24 Feb 08: Too late for the streetscape? • 15 Feb 08: "It really could be something." • 18 Jan 08: Estuary of Dreams • 11 Jan 08: More than shelter • 10 Jan 08: Nature's balance • 6 Dec 07: Snake uprising • 4 Dec 07: A Junction that ought to be • 6 Nov 07: Around the Mulberry Tree we go • 29 Oct 07: Wondering about wandering • 5 Oct 07: No other way • 21 Sept 07: Here is the Possible City |