10 January 08: The Possible City

Nature's balance

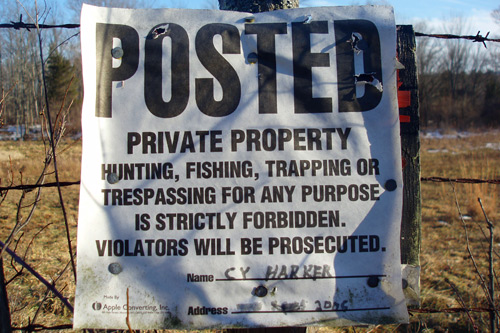

by Nathaniel Popkin January 10, 2008 The Old Mine Road, which starts at the Hudson River and continues to the Delaware Water Gap, is one of the first commercial highways in the US, in use for at least 300 years. Much of the New York portion became US 209. But in New Jersey it passes through the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, where the road is lightly paved or gravel, narrow, and scenic. Otherwise dotted with mostly abandoned farm houses (farms taken for the failed Tocks Island Dam project in the 1970s), rushing streams, corn fields, and meadows, in certain sections the road passes within eye-shot of the Delaware, its islands, its turns, and the cliffs that rise on the Pennsylvania side. It's a less epic landscape than the Hudson but more intimate and moving. Here, more than anywhere else in the mid-Atlantic region, one feels the lush belly of the earth in its melancholy tension with the passage of time. It is a place of ruins; when the federal government condemned farms for the dam project (which was to have active recreation uses as one of its bi-products -- think miles of parking for summer day-tripping families) it left a landscape suspended in time. Camps, farmhouses, outhouses, stone walls, gardens, and barns were left. Some have fallen and others bulldozed, but not the resentment of a people whose way of life was, they believe, condemned. Oldtimers in Sussex and Warren counties on the New Jersey side and Pike in Pennsylvania therefore despise government, the Feds especially. The resentment endures despite reason, coalescing with the reactionary conservatism of our times. Cy Harker was one of those oldtimers; his farm, one of the few privately-held working farms within the park's boundaries, straddled the Old Mine Road just above Peter's Valley, the artists' colony. His stone house with sky blue trim and barn, his ancient dog, the curve of the road, the tilt of the earth made Harker's farm a popular spot for photographers and landscape painters and Harker himself an iconic figure. He'd refused to sell to the Feds, after all, and in his nineties still worked his land. But late in 2006, the old man lost control of his tractor. It ran him over and he died. His heirs sold the farm to two local brothers, Aaron and Matthew Hull, and their wives. The Hull family had endured the failed dam project and the subsequent designation of the recreation area. And despite the positive impact of the park on the area, they still carried resentment, an irrational mistrust of "government," a fear that colored their view of the world. They own the land on each side of the road, they say, and threading the regulatory needle, claimed its ownership. So this fall they installed gates across the Old Mine Road, one at south end of the farm, the other, 300 yards on, at the north. Having walked those 300 yards many times, I was dumbstruck last week when taking a winter hike we discovered the gates. My wife and I had to instruct our daughter Lena that walking around the gateposts wasn't breaking any law, merely asserting a right to traverse an ancient path. "It's a road!" I exclaimed. What is a road, but a testament to the need we have for one another? This one particularly, in use since the seventeenth century, is part of the nation's patria, an early nexus of commerce, culture, and community.  One might lose sleep thinking about these gates. Imagine, for example, that each of the landowners on either side of the Hull farm did the same and blocked their part of the road; the road -- society itself -- would lose all meaning. So this is sabotage of the public sphere by private whim, never mind that the landowner on either side is the US Department of the Interior. Never mind, indeed, that in winter the Park Service itself closes an uninhabited part of the road a mile or so on. Having been underfunded for so long by conservative governments, it doesn't have the budget to keep it safe. The Hulls say the gates are needed to protect their safety and privacy. This is like President Bush saying he's invaded Iraq to spread democracy. They're words, merely, meant to cover actions, in this case ones they know are possible only because their farm is surrounded by public land. Bill, a retired engineer who leases federal property just to the north of the Hulls, is unlikely to block off his portion of the road, trapping them in. So this is a dare of sorts meant to force the federal government to take strong action, thereby confirming what they already believe. Some 70 miles downstream, our parks too, suffer the imbalance between private initiative and public good. Only here in Philadelphia -- aside from the occasional Ohio House as café project -- there is too little messy personal ambition and too much high-minded public good. The result is abundant nature -- we've nine environmental education centers in the city alone -- too little money to manage it, and too few people to enjoy it. The imbalance is the legacy of diverse historical forces -- from Penn's original ideas to the shrunken tax base -- and critically, a shrunken idea of what city parks can be. This last point is what Dennis McGlade, president and principal at Olin Partners, the landscape architecture firm, and I are discussing as we sit on the new granite seat wall at Lubin Plaza. (Andropogon Associates, not Olin, designed the plaza, which McGlade thinks is "lovely.") McGlade is an empathetic man with short white hair and throwback glasses. He is a pluralistic thinker with a keen sense of plant systems and human psychology. To him, tree placement has as much to do with aesthetics as it does with ecology, plant biology, and human nature. And the question of nature in the city reveals connections among road salt, blacktop, empty lots, roofs, population density, and rainfall. "Damn Thomas Jefferson," says McGlade, meaning that in comparison to people around the world, Americans aren't comfortable in public spaces. It's the planner -- and landscape architect's -- job to create spaces that make people feel good, but Americans don't live in public. A park he's working on in Beverly Hills is threatened because no one is sure who will use it. But McGlade concedes that recently a new kind of urbanity has emerged in Philadelphia and other American cities, and he is hoping this will allow us to make parks and other public spaces more dynamic. For our sake, we better hope he is right. A cosmopolitan city needs parks because they are grounds for socializing. "Why parks?" asks the writer Bonnie Menes Kahn in her philosophical exploration of the tolerant city, Cosmopolitan Culture. "Why public parks . . . Public life is a social creation and it in turn creates a cosmopolitan culture." If one of our goals is to make Philadelphia more cosmopolitan then we'll need to make certain parks -- squares especially -- more engaging. That means altering the balance between public and private uses -- or more accurately reclassifying things. Food vendors, cafes, balloon men, musicians, though private, support an open-air social life, which according to Kahn is an important ingredient in a cosmopolitan city. In most of the world -- with varying public-private considerations -- city parks and squares (streets too) are designed to entertain, which in turn makes them busier and therefore more fun and safe. Kahn says, too, that a little green goes a long way -- and in that regard Philadelphia with its hundreds of small squares provides just the right quotidian respite from the ills of the grid. Ask any parent and they'll tell you how much children are drawn to the city's parks. A few tall trees is all it takes. Add regular activity -- pretzel vendors, newspaper kiosks, water ice carts -- on top of the growing list of seasonal uses -- movies, concerts, festivals, barbeques, Christmas tree lighting ceremonies -- and we might come to realize that our city is fun and pleasant to live in. The seasonal uses have mostly developed in an ad hoc, bottoms-up manner dictated by neighborhood organizations and friends of park groups. The Recreation Department, for its share of neighborhood parks (given the arcane division between Rec and the Fairmount Park Commission, park management is split), picked up on these desires and now provides support for events and movies. But city life requires more consistency -- right down to daily routine. If we want public spaces to be part of our lives -- and why else live in the city? -- then we need to make them attractive and engaging everyday. This requires vision and, in a cash-strapped city, the ability to leverage assets already in place. I'd like to offer two examples, ways in which small green spaces can do more than grow trees. McPherson Square (managed by the Recreation Department) is a classic city park between Clearfield and Indiana on Kensington Avenue. It's an equidistant three blocks from the Somerset and K&A El stops and most critically, in the center of the square is a neo-classical Carnegie-built branch of the Free Library. Immigration here means the population, for the first time in decades, is growing. It is poor and last year there were two homicides in the immediate vicinity of the park, seven shootings overall. And despite a pretty fine urban fabric, it suffers from the usual abandonment, empty storefronts, and neglect. Now imagine how important the tiny park is to that part of Kensington -- in the densely populated K&A, where parents complain there is nowhere for their children to play it's one of only a few spots of green. It's so important and, unfortunately, characteristically overlooked. Yet it wouldn't take much. The library branch is already there: people come and go all day long. Add a vendor or two with electrical hook-ups and tables -- good empanadas might be enough of an attraction -- improve the lighting in the park and on the streets around it (it ought to shine like a beacon), and ask the library to engage in the green space around it. Finally, so that residents know they can come to the park to feel safe, make the park part of a community police officer's regular beat -- or better, install a small guard house. Headhouse Square -- the revived market shambles extending into the parking lot -- is McPherson's opposite. Where the Kensington park glows green amidst gray, Headhouse is the black hole in old Philadelphia red. What a missed opportunity! "South Street is fine," says the artist and builder Jeff McMahon, "all it needs is a frame." Or a chance to breathe; perfectly proportioned Headhouse is that chance -- to provide genuine public space for heavy socializing, to stitch South Street to Society Hill and Queen Village, to give context to the market shed and the retail along Second Street. Yet the current square is dismal, crumbling, and poorly lit. A little green goes a long way, remember. McMahon says add another story to the parking garage above Cosi and remove the cars that now inhabit the southern section of the square; green it. Then enclose it so that late at night it can be locked.  "Density is our salvation," says the landscape architect McGlade, and in Headhouse of course, there's enough density of everything to make it a dynamic and transformative public space. But McGlade has in mind the efficiencies in energy, transportation, and land use brought about by density. "The best thing we can do [to make Philadelphia a green city] is get people back," he says as we stroll west on Walnut Street near Rittenhouse Square. The best thing we can do for Fairmount Park is to increase the number of people living around it so that the park itself -- East and West, Pennypack, Cobbs Creek, Wissahickon, FDR, and all the neighborhood squares -- is part of the everyday lives of more people. "I was in West Park, around the horticultural center on a perfect Saturday this fall. It was gorgeous, but no one was there, maybe because there really isn't much to do. I couldn't even find a vendor to buy Isaak (my son) a hot dog," I complain to one of the Fairmount Park Commissioners, Farah Jimenez, who is also executive director of Mt. Airy USA. It's a cold morning in December and we're sitting inside the Hausbrandt Café on Fifteenth Street. Jimenez, who has a kind of Frida Kahlo sensibility for clothing and jewelry, is sipping tea. Since arriving in Philadelphia over twenty years ago Jimenez has expected more of the city than it's usually able to deliver. Now in Mt. Airy, she's getting the chance to help the northwest realize its leafy -- and cosmopolitan -- potential. With Fairmount Park she sees an opportunity to turn a liability into a glimmering asset.  "I have always dreamed there should be a Tivoli in Fairmount Park," she says, referring to the amusement and entertainment districts in Copenhagen and Stockholm. She says this not only to agree with me but because since joining the Commission she's come to realize the breadth of the park's resources. Her role, she says, is to help instill a perspective of asset management, rather, I suppose, than the current disaster management. McGlade supports inserting commercial uses into parks. He'd probably agree a Philadelphia Tivoli is an inspired idea, but sees such a measure as a last resort in a political climate that demands low taxes. "Charge 2% more in taxes and you wouldn't need commerce in parks," he says. But Philadelphia, as city officials and other analysts explain to me, has no money. Jimenez runs through the litany of structural problems: the old buildings, the ones in use leased for $1 a year often as a result of political deals (including the Mann Music Center, which also doesn't pay for electricity or grounds maintenance), zero councilmanic-prerogative funding as the Recreation Department enjoys, the diverse set of well-intentioned friends groups that were created to help compensate for funding shortfalls but which sometimes distract from and drain the mission, and poor branding. This is the disaster Jimenez hopes to turn into an asset -- impossible without significant public-private partnerships. "There used to be 700 plus park employees; now there are little more than 150. At 1950 funding levels adjusted for inflation the park budget should be $70 million," Jimenez tells me. "Today $12 million covers the employees. Mayor Nutter has promised $50, but we'll see if he can deliver." Jimenez is enthusiastic about the park's staff, who she says is creative and dedicated. As a park user, I'm amazed the park looks as good as it does given limited funds -- this alone is a testament to the city's resilience. Jimenez thinks Cynthia Temple, the manager of trust and custody funds, the person whose job it is to manage the park's vast holdings, is using sophisticated financial techniques and is "a really good CFO." But Fairmount Park hasn't received capital funding in two years, which means maintenance is deferred and conditions are worsening. My guess is that Mayor Nutter will address that in his first budget. We'll keep an eye on the budget proceedings later this month. An asset-based approach is what makes the park's Centennial District project enticing; it's why I like the adaptation of the old visitor center on Sixteenth Street into the Park's welcome center (though a caveat, the execution is terrible; there are no maps (!), no schedules of events, and the woman at the counter has nothing to say). But both projects fail if we can't find a way to get people into the park. The welcome center works if you can get all the information you need and if right there you can get on a shuttle to various park locales. A shuttle system -- perhaps an adaptation of the park house tour trolleys -- may be the only way to compensate for a park that isn't central but sprawling and disconnected and only begins in Center City. How do I get to the Japanese House or Stenton Mansion or Smith Playground otherwise without a car? If we can't answer that then we haven't figured out asset-based planning. Nature is part of the city, not its opposite. A civilization, after all, finds ways to harness the earth, exploit its power, temper its fury. For 200 years of our history we tried to manhandle our natural environment -- and it made us rich. Now it makes us sick. Nature, of course, inspires, allows meaningful reflection, refreshes the spirit. A life without it is grim, indeed. As McGlade responds to my question, "So what do we do?" it becomes clear he decries the lockstep focus on "sustainability." The green city movement rings to him as hollow fashion. More important is to understand that the city is a system and that we as its stewards have the responsibility to manage it. To him this means choosing street trees that can withstand salt (we get more ice than snow nowadays and road salt is a fact of life) and plant them so that the roots can grow; minimizing asphalt, planting on in-fill sites, and capturing storm water treated by certain water-cleaning plants grown on city roofs. He describes to me the "heat column effect," the result of which is that rain storms can't get to the city. We get the heat, the humidity, but little rain, placing further stress on plant systems. "The earth responds to careful planning," seems to be McGlade's approach, which is intentionally non-doctrinaire. Given the fiscal climate, starting small is our only choice. This is precisely how Adam Levine, who is the Water Department's archivist, believes we ought to proceed. Levine is the soft-spoken and self-effacing stream expert, who says you can't know Philadelphia's history without understanding how it filled streams, placed others in culverts, graded streets eliminating natural contours, and assembled a sewer system -- a marvel in its day -- that combines waste and fresh water, treats it all and dumps it back in the river. I've asked him to tell me if it's possible to unearth our ruined streams. He's careful, jaded by years of Philadelphia's reality; he isn't going to sell me on ideas that aren't possible -- though given his collection of landscape paintings and artifacts he must see another, more lovely city before him. There are a few possibilities, test locations where Philadelphians might be able to reverse the engineering feats of the nineteenth century, and see (feel, splash, jump over) glimpses of the natural heritage. Given the recent success of the renovation of Saylor's Grove in Germantown, he cites Indian Creek in West Philadelphia, springs at the Awbury Arboretum, the Poquessing in the Northeast, and the Pennypack, where there are dams still to be removed. He mentions the greenway along Frankford Creek, Tacony Creek Park, and League Island, where some attempts have been made to reclaim tidal marshes. But Levine admits these are small -- almost insignificant -- steps. Each project depends on local stewardship, which is the blessing of this parochial city -- and its curse. Perhaps small projects will never add up, one reason for Levine's reticence. Dreaming can be painful, after all, so it's natural to keep dreams within reach.  Think big -- and, well . . . your work might tumble into the Schuylkill River. Beginning in 1986, the idiosyncratic painter Tom Chimes and his friend, the bristling, giant religious poet Steve Berg invented and installed a piece of public sculpture along the east seawall of the Schuylkill -- the 1,200 feet heading south from Carl Milles' sculpture Playing Angels. Sleeping Woman is a poem of Berg's inscribed in blocky black typeface of Chimes' design. The woman of the poem is the river, ever-present in the lives of these two lifelong Philadelphians (Chimes, whose son Dmitri owns the eponymous restaurant, grew up in Strawberry Mansion with a view of Memorial Hall). gusts scribble of leaves cloud scrawl unpredictableDid you know there is an epic poem inscribed along the river? One you can read in edible pieces while you toss a Frisbee? Berg is one of the most influential poets of our time; Chimes a master; the collaboration, supported by Penny Bach of the Fairmount Park Art Commission, was intense public art. But just before the unveiling ceremony in 1991, the seawall collapsed. Berg at first was devastated, but Chimes was immediately philosophic: this only reinforces the power of nature, doesn't it? Berg became convinced. Leave it. Both men have a fatalistic quality about them. So blank stones were installed in place of lost words, and since then the remains of the poem have been covered by sediment and weeds. It's intellectually -- perhaps emotionally -- honest. The collapsed wall has become part of the art, I agree. But a city doesn't leave things to nature. It seeks the balance that advances the civilization, which is just the challenge before us. I want the poem back; it is ours and it is beautiful. Letting it go is an act of retreat, the admission that we're powerless -- a sign that nature's out of balance. * * * For more information on the closing of the Old Mine Road, please see HERE and HERE. –Nathaniel Popkin nathaniel.popkin@gmail.com For more on The Possible City, please see HERE. For Nathaniel Popkin archives, please see HERE, or visit his web site HERE. |

|

• 6 Dec 07: Snake uprising • 4 Dec 07: A Junction that ought to be • 6 Nov 07: Around the Mulberry Tree we go • 29 Oct 07: Wondering about wandering • 5 Oct 07: No other way • 21 Sept 07: Here is the Possible City |