|

When William Penn and his Surveyor General Thomas Holme first laid out the city of Philadelphia's street plan, Penn's vision was that of a city that grew along the banks

of the Delaware and the Schuylkill Rivers simultaneously. But from early on it was clear this wouldn't be the case and the dream was abandoned around 1684. The Delaware

was to be Philadelphia's main port of entry and remains so to this day. Early Philadelphia huddled along the banks of the Delaware and slowly expanded westward in the

coming decades. As late as the 1840s, people of means who built their residences west of Broad Street were considered pioneers. The land over the "hidden river" would

remain a collection of small villages, most of which have lent their names to the various neighborhoods now it their place.

When William Penn and his Surveyor General Thomas Holme first laid out the city of Philadelphia's street plan, Penn's vision was that of a city that grew along the banks

of the Delaware and the Schuylkill Rivers simultaneously. But from early on it was clear this wouldn't be the case and the dream was abandoned around 1684. The Delaware

was to be Philadelphia's main port of entry and remains so to this day. Early Philadelphia huddled along the banks of the Delaware and slowly expanded westward in the

coming decades. As late as the 1840s, people of means who built their residences west of Broad Street were considered pioneers. The land over the "hidden river" would

remain a collection of small villages, most of which have lent their names to the various neighborhoods now it their place.

Amidst the hamlets of West Philadelphia in its early incarnation were pleasant pastoral scenes, famous taverns and a few notable estates, among them the abodes of John

Bartram and William Hamilton. Things slowly improved for Blockley Township, as it was then known. The first bridge connecting West Philadelphia to the rest of the

city was constructed in 1800 at Market Street. Shortly after it was built it caught fire and a sturdier one was put up in its place in 1805. The construction of many

charitable institutions such as the Blockley Almshouse (1834) helped to make West Philadelphia an integral part of the growing city.

Things began to change more rapidly after 1854, when the all of the small villages of Philadelphia County were consolidated under the City of Philadelphia. New bridges

spanning the Schuylkill along with horsecar lines introduced in the 1860s made getting to and from West Philly easier than ever. This allowed for developers to snatch up

former farm land and create palatial estates and villas for the city's growing merchant class. One of the first was Hamilton Terrace along 41st Street, designed by noted

architect Samuel Sloan. Another was Woodland Terrace. Built in 1861, the Italianate villas were also designed by Sloan. The twin homes, which are still standing, were

intended to look like one huge villa.

Sloan was not the only important architect of his era to leave his mark on the area. Others came and created memorable monuments to their craft. Numerous buildings, both

public and private, bear silent witness to their skillfulness. Those familiar with Philadelphia's architecture know the names well. Furness, Hewitt, Trumbauer, Hale, and

Wilson are all among the many contributers to West Philly's rich architectural legacy. The fashionable styles from the early Italianate to the turn-of-the-century

Colonial Revival style attest to the refined living sought by the wealthy residents of West Philadelphia. Costly building materials and attention to detail were the

hallmark of fine Victorian home building. The captains of industry spared no expense in letting the world know, "I have arrived."

As modes of transportation improved, West Philadelphia continued to expand and grow westward. The coming of electrified car lines and the 1876 Centennial Exposition

helped West Philadelphia emerge from its isolation. No doubt the most lasting contribution to the area was the arrival of the University of Pennsylvania in 1872 followed

by Drexel University in 1891. The latter half of the 19th century saw explosive growth. Speculators and developers were grabbing land as fast as they could. The area

was quickly losing its rural quality and becoming Philadelphia's bedroom community. The Streetcar Suburb was taking shape.

With the coming of the 20th century, West Philadelphia was now a major player in the Philadelphia social and economic scene. The universities and the burgeoning white

collar class put more demands on the city's transit system. A more modern method of transportation was needed. Enter the Market Street Elevated Line in 1907.

With the El, expansion happened at an even faster pace. New business districts propagated at the El stops along Market Street. New rowhomes for the middle class and new

immigrants sprung up almost overnight further and further away from the banks of the Schuylkill. Now it was possible for a person making an average salary to live as far

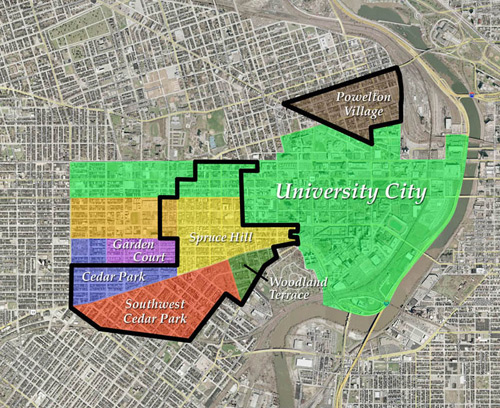

west as 60th Street and commute daily to Center City. Following World War I, the automobile bursts its way onto the Philly scene and a previously inaccessible patch of

land in the district was developed in the 1920s as Garden Court. As the 20th century progressed, the streetcar gave way to autos and buses.

The neighborhoods that constituted the Streetcar Suburb of West Philadelphia have seen many ups and downs in recent decades. Despite neglect, blight, and strong disfavor

among the architectural elite, the classic architecture has largely endured. Now there is a new found appreciation for the old time buildings. The neighborhood has seen

an influx of new residents recently and lots of rehabbing has been taking place. Some of the longtime members of the community are feeling forced out the shocking rise in

property values. Despite the gentrification of late, there is a good mix of residents in the area. White anarchists, African immigrants and Penn professors can be seen

rubbing elbows at Clark Park or the Green Line Cafe. As the regional anchor, the University of Pennsylvania with its ever expanding campus seems to portend a solid future

for the district. In the meantime, the neighborhoods of University City beckon for your exploration. Be it by trolley, streetcar or on foot, you will find it a most

rewarding journey.

- JMM

GO TO PHOTOS

|